Away from the storm: Disaggregation of the semiconductor value chain.

Away from the storm, other companies needed processors. ATM makers needed processors to vend out money. Elevator makers needed them, well, to elevate people. CAT Scanners, pneumatic drills, weighing machines, heart rate monitors, flash memory vendors – all needed simple, relatively uncomplicated, low-cost, low-power, custom silicon.

There was a parallel, simpler market that was thriving. With three decades of existence, it was getting sophisticated in its business models, its manufacturing and its products. While Intel was a one stop shop, there were many players in the eco-system who were slowly crawling their way around the treasure fort of Intel.

We are explaining this through three companies – Apple (as a microprocessor company), ARM and TSMC. We start off with ARM Holdings, and cover it in this blog and the next.

Here is a quiz for you: Who was the original investor (along with Acron computers) for this newly formed esoteric start up called Advanced RISC Machines (’93) – which turned out to be the ARM as we know it?

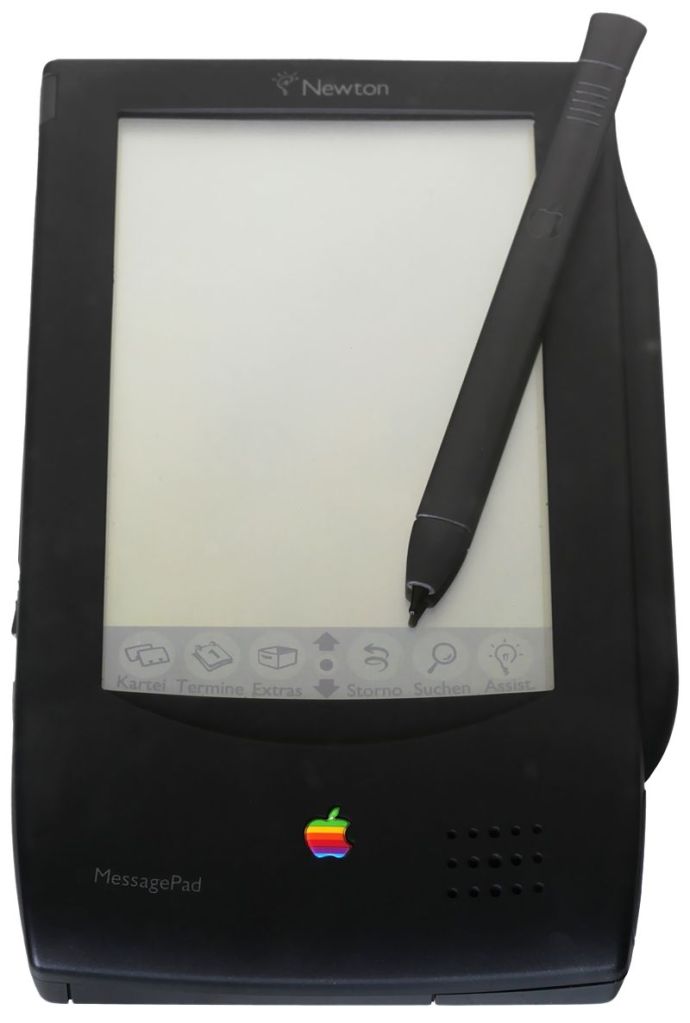

OK. It was Apple. They brought in $3M for 43% stake. They exited for billions by ’99. Apple’s first hand held, the Newton was one of the first devices powered by ARM.

ARM Holdings: The disruptor of the disruptor

Suppose you needed a micro-controller to design your latest digital camera or a GPS device.

You are working on a very tight budget, competitive the industry is. You want to take an existing micro-processor design, optimize it a bit and get to your design quickly and economically.

Who will give you those base designs? In comes ARM. The do not manufacture any micro-processors, they just license their Intellectual Property for others to customize, manufacture and use.

Because ARM designs powered digital cameras, GPS devices and the like, it was very power efficient. Because the customers worked on small budgets, it was economical. Because it allowed others to design their systems and integrate them into one chip, they were very flexible. And because they didn’t spend big money on fabs, they had operating income >50% of their revenues. Just that their margins were not in billions, it was in millions.

Fast forward 20 years just check out the devices on my table.

Every device on my table, except the Sheaffer pen has an ARM chip inside. Then may be, the Sheaffer pen is not a device after all. An ARM chip is found inside every (non PC) device, almost by definition.

Helping OEMs own the processor design

In the 90’s decade, ARM were selling their design IP and instruction sets to different Original Equipment Manufacturers. In critical industries like healthcare and video processing, the OEMs wanted to own the entire IP – including the core processor. This is very different from the PC industry where the core IP of the processor is owned by one of the suppliers, Intel. So, they invested towards building their processors based on ARM Core.

ARM (’90), was progressively improving the design and licensing the new design to the firms like Nintendo, Samsung, Nokia, Motorola, TI and others. Some of them were not making any equipment, but focused on making specific purpose chips – like Samsung.

Sweet spot in 2007

In 2007, the ARM and Samsung combination were in a sweet spot: they were in the right place, with the right business model. Their chip together had sufficient processing capability. Samsung had the manufacturing scale. The prices were appropriate as it didn’t carry the x86 premium. The processors were optimized for power, that the devices can last an entire day.

So, in retrospect, it is no wonder that an ARM based Samsung chip (Samsung ARM 11 RISC) was part of the first iPhone design.

Steve Jobs Introducing The iPhone At MacWorld 2007

ARM makes quantum progress

Suddenly, the ARM core and ARM instruction set were powering the new age computing devices – smartphones. They didn’t look like a personal computer – so Intel and the PC vendors didn’t see them as a threat. They made moves that were not deep enough to unseat a creeping, crawling competitor who positioned themselves in this space over two decades of patient maneuvers.

Android: A Dream Debut:

Android was acquired by Google in 2005 and suddenly it found its purpose in 2007. To be iPhone’s competitor. So, Google scrambled up the touch interfaces and network handling. They worked with other OEM’s to launch the first Android phone.

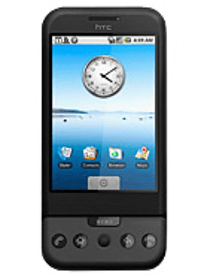

HTC Dream was launched in 2008, with a Qualcomm processor based on ARM v6 design. Qualcomm integrated the smartphone modem inside the silicon, along with the core processor.

The rest, as they say is history. In 2017, Google announced 2 Billion Monthly Active Devices on Android. There were just two other application eco-systems with more usage – Google itself and Facebook. Almost every device had an ARM IP component in it.

The attack on the treasure fort had begun.

In this timeline, ARM added features that made it more like a computer processor

- With more computing, more memory reads were required. Like Intel did in 80386, ARM introduced the Memory Management Unit in its processor designs in 2004. Like the 80386, they were a big hit.

- ARM was a 32 bit CPU until 2014. The maximum RAM any CPU made from ARM core could address was just 4GB. In 2014, ARM introduced the 64 bit architecture that increases infinitely the amount of memory that can be addressed.

- Virtualization, Pipelines to carry the data efficiently, Instruction fetch channels – ARM kept on adding more capability to achieve faster and faster speeds.

Deployment accelerates

Fueled by the mobile devices growth and a strong product offering aimed at the segment, the deployment base of ARM was accelerating.

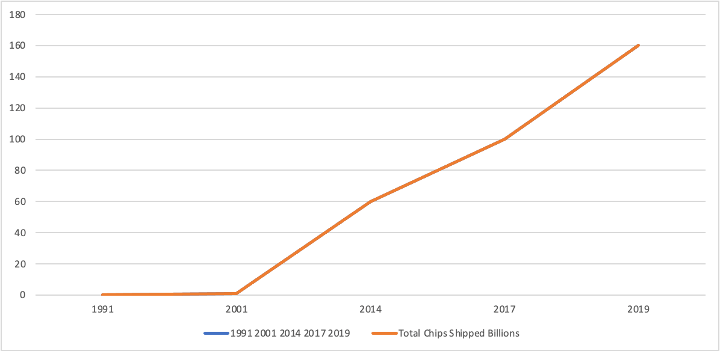

Like late bloomer, the ARM eco-system started avalanching with acceleration of smartphones and other devices. It took ARM a decade to ship the first 1B units. In the next decade, they shipped 40B units. By 2019, ARM eco-system partners had deployed over 160 Billion chips – the last 60B in just the last 2 years.

And there is no sign that the momentum will stop.

—

Next: Written on Rosetta Stone #8: ARM twisting into adjacencies